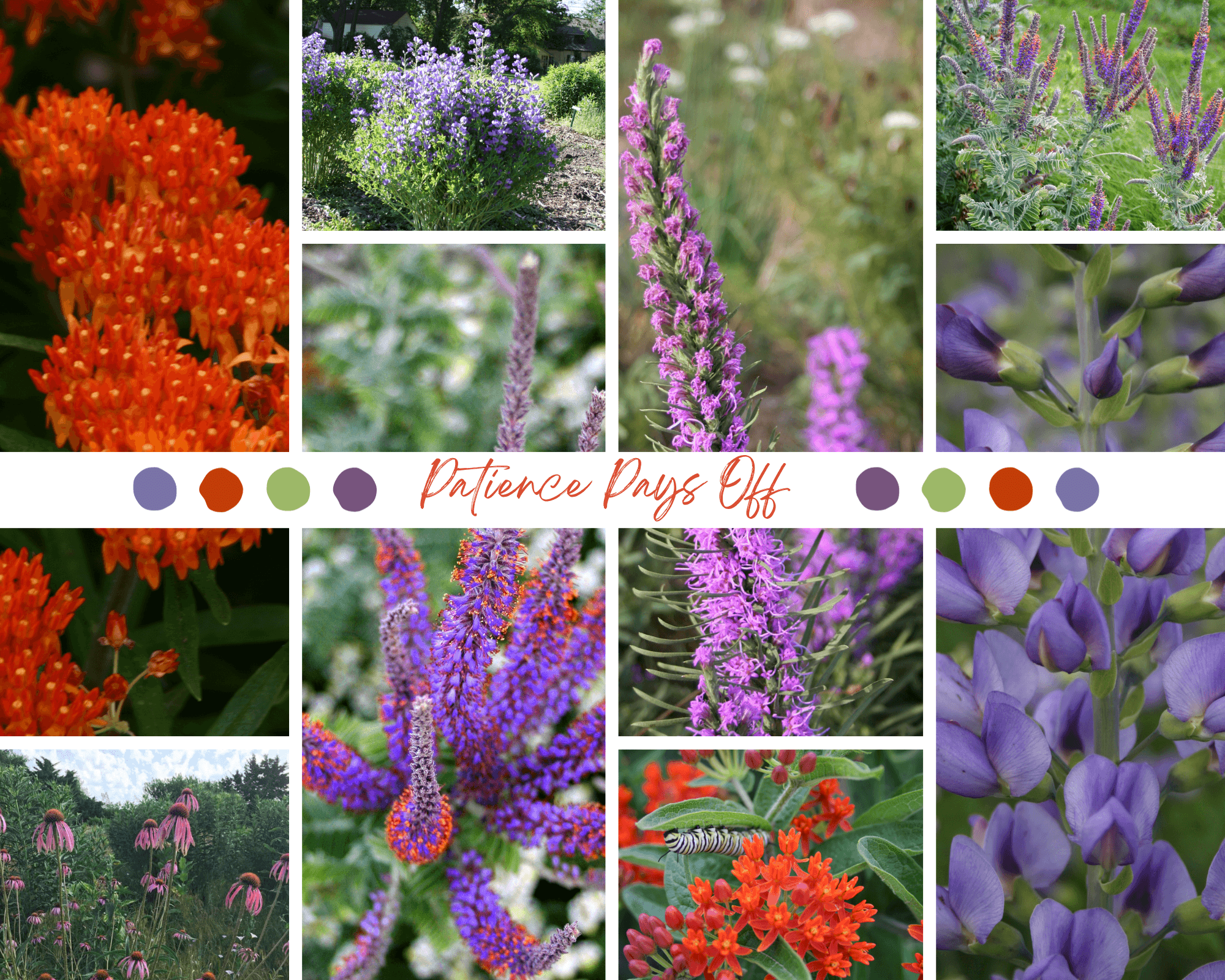

Images pictured clockwise from top left: butterfly milkweed (closeup), dwarf blue indigo, dotted gayfeather, leadplant, dwarf blue indigo (closeup), butterfly milkweed and monarch caterpillar, leadplant (closeup) and purple pale coneflower.

Some plants are worth the wait. Here are five perennials that require a bit of patience to get established but offer big dividends in the end.

Leadplant (Amorpha canescens) is a prairie shrub in the legume family that offers both beautiful blooms and interesting foliage. Bursting with sprays of purple spikes with orange stamens in July, the flowers don't last long, but the silver-green leaves continue to offer lots of visual interest throughout the spring, summer and fall.

A woody shrub, leadplant can take a few years to mature, but the good news is, it's long taproot (up to 15 feet!) makes it extremely drought-tolerant and long-lived, so once you get it established, you'll enjoy its beauty for a good long time.

Leadplant grows to a height of 2-3 feet and thrives in medium to dry soil (it's not picky about sand, gravel, loam or clay) and full sun. It can tolerate partial shade, but tends to be more leggy and sprawling, rather than upright, in shady conditions.

Leadplant flowers attract tons of bees, butterflies, moths, beetles and other beneficial insects. It's deer-resistant, but rabbits like to munch its tender, young leaves, so put a cage around it during the years it's getting itself established.

One other fun fact about leadplant: its super tough, deep roots made pioneer plowing difficult, causing early settlers to dub it "Devil's Shoestrings."

Dwarf blue indigo (Baptisia australis var. minor) is a perennial native wildflower that is similar to, but smaller than, its cousin, Baptisia australis (sometimes called false indigo). This shrubby beauty grows between 3 and 4 feet tall and produces a prolific display of vibrant, lupine-like purple spikes in May. These blooms are especially valuable to bumblebees, as the bloom time coincides with the emergence of hungry bumblebee queens from their winter hibernation.

Dwarf blue indigo can take a few years to get itself established in the landscape (especially if sown directly from seed). But trust us, the wait is worth it -- eventually the plant will mature into slowly expanding clumps with deep and extensive root systems, which make it drought-tolerant and able to thrive in hot, dry conditions and poor soils (including sandy, rocky and clay).

Another benefit of dwarf blue indigo is that like leadplant, it's a member of the legume family, so it forms a symbiotic relationship with the nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria rhizobia. Rhizobia attaches itself to Baptisia root hairs, making nodules all along the roots that then allow the rhizobia to form what's called an "infection thread" into the plant. Once inside the plant, rhizobia converts atmospheric nitrogen (which is not a form that can be used by plants) into a useable form of nitrogen. In return, the rhizobia gets nutrients from the plant.

Butterfly milkweed’s (Asclepias tuberosa) long-lasting, bright orange flowers make it one of the most popular milkweeds. True to its name, this herbaceous perennial attracts legions of butterflies and is an important host plant for monarchs and queens.

Butterfly milkweed matures at a height of about 2 feet and thrives in full sun and dry to medium sandy or loamy soils (it can also tolerate clay). Though it offers a long bloom time (June-August), it can take up to three years after planting to flower. Unlike other milkweeds, butterfly weed does not have milky sap, but it does produce seed pods that release fluffy-tailed seeds that disperse on the wind. It’s also considered mildly toxic to humans and to animals but is generally safe to plant around children and pets.

Dotted gayfeather (Liatris punctata) is native across much of the Great Plains and prized by gardeners for its long-lasting lavender wands of blooms that attract many varieties of butterflies, native bees and birds. Its very long taproot (up to 14 feet) makes Liatris punctata the most drought-tolerant of the gayfeathers.

Dotted gayfeather devotes most of its energy and growth to its root system in its early years, which means it is slow to become established and sometimes slow to bloom. Even when it’s fully established, dotted gayfeather stays dormant later in the spring than other plants, so be patient and don’t give up on it! Maturing at a height of about 2 feet tall, it prefers full to partial sun and medium to medium-dry soils.

Pale purple coneflower (Echinacea pallida) is an iconic Midwest prairie flower with drooping, daisy-like blooms that attract plenty of pollinators in early spring. The blooms give way to seed heads later in the summer that attract goldfinches and other birds.

Like dotted gayfeather, Echinacea pallida’s very long taproot makes it highly drought-tolerant but also slow to establish itself in the landscape. Once established, it’s highly adaptable, tolerating drought, heat, humidity and poor soils. The only environment pale purple coneflower will not thrive in is one that is too moist or very poorly drained.

Maturing at 2-4 feet tall, pale purple coneflower's bloom color can range from the palest pink (nearly white ) to a deep rose. It typically looks best planted in a prairie-type landscape with mixed grasses and other wildflower perennials and freely self-seeds if at least some of the seed heads are left in place.